|

Targeted therapies

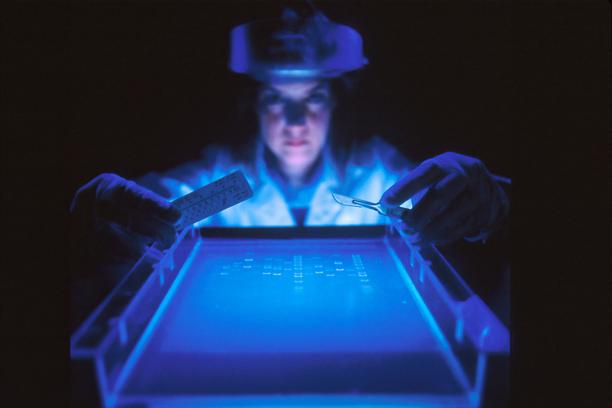

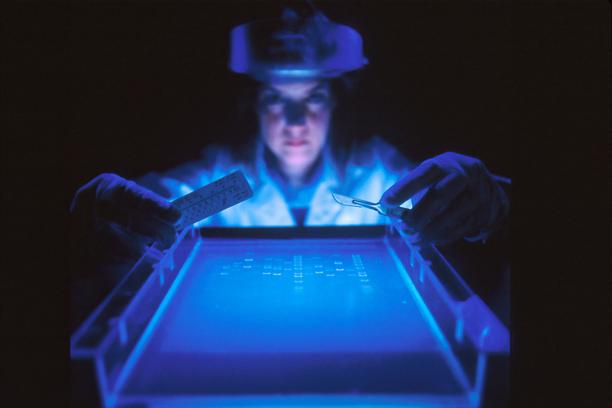

The science that underlies cancer therapies has changed from chemistry to genetics. Chemistry fuelled the growth of the pharmaceutical industry in the early to mid 20th century, which has now matured. In the late 20th century genetics gave birth to a new biopharmaceutical industry, which is growing rapidly.

Biopharmaceuticals, based on genetics and molecular science have given rise to targeted therapies and personalised medicine. This tailors medical decisions, practices and therapies to individual patients and corrects abnormalities at a molecular level. Such therapies offer the potential to reduce cancer’s unacceptably high mortality rates and raise its unacceptably low detection rates.

Several targeted therapies have been approved. The most well known is trastuzumab, which is marketed as Herceptin and used in early stage breast cancer patients with high levels of the HER2 protein.

Improved global communications and a cure for ovarian cancer

Targeted therapies require significant data flows between scientists and doctors: the bench-to-bedside approach. Currently, at best, this is inefficient and at worse, it’s simply not done.

Breakthroughs in ovarian cancer research will not occur without significantly improving:

1. The collection and standardization of vast clinical data sets from different geographies

2. The creation and development of large-scale interconnected tumor banks with standardized tissue samples also from different geographies

3. The management and distribution of these vast clinical data sets and tumor samples to scientists able to combine genomic and clinical data, which is a necessary prerequisite for genetic, epigenetic and proteomic analysis.

Ovarian cancer breakthroughs will not come from professional cancer associations, nor from the endeavors of small charities and nor from doctors alone. All are inexperienced in global communications and big data management. Breakthroughs are more likely when well-resourced global organizations with highly developed big-data management skills get involved in medical research.

In September 2013 we came a step closer to this, when Google co-founder and CEO Larry Page announced that he is planning to launch Calico, a new company to use Google’s data-processing strength to shed new light on age-related maladies.

In a similar vein, Jonathan Milner the biotech millionaire and a founder of Abcam, one of the world’s largest retailers of research antibodies, is backing a venture to create a Wikipedia of genetic disease data to help diagnose an array of uncured conditions.

Key takeaway

Maurice Saatchi should consider trading his ermine robes for shorts and T-shirt and head to Mountain View, California and combine his considerable communications skills and energies with those of Larry Page in an endeavour to, “change the ways medical scientist create, share, communicate, collaborate and do research.”

|